Powerful leaders? by Marcus Honeysett exposes and explores how people in positions of authority in the church can be tempted away from a biblical model.

The book provides, he says somewhat mildly, “a diagnosis of common symptoms to increase awareness and suggest some basic first aid” p.3, but also, more alarmingly, portrays in some detail what unchecked, self-serving power looks like in the hands of unaccountable leaders ignoring written policies and procedures and poorly monitored by the governing body.

This often starts from a wrong perception of the role of leaders, not dissimilar to that of a CEO, understood as ‘leadership is influence’ and characterised by a set of skills and competencies. He points out that Christian leaders are characterised by servant leadership. They are there primarily to shepherd the sheep, caring and nurturing, not ‘lording it over them’ (Mark 10.42). If we read the apostle Paul rightly, we see that weakness and repentance is part and parcel of godly leadership - he boasted in weakness not strength. His character, conduct and decisions were transparent - “he allowed his own life to be an open book (2 Timothy 3.10)”, p.17.

As the Gafcon GB & Europe editorial comment on Jerusalem Declaration article 7 makes clear, “the word ‘priest’ should not denote any kind of mystical spiritual ability, and certainly not being above correction. Christian leadership should be characterised by servanthood and humility, not abuse of power or pursuit of status.”

Yes, authority is appropriate (as conferred formally by the role and relationally through gaining trust) but the limits of its mandate should be known by all. Honeysett recognises there are differences within denominations and independent churches but “adding burdens, demands and expectations that Scripture does not”, p.26, oversteps the ‘Scripture alone’ authority boundary, that is, what is commanded in Scripture. Leaders should not command and insist on beliefs and behaviours on the basis of their own personal authority.

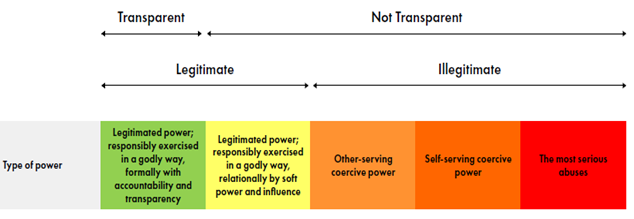

Just in case readers cannot imagine how it goes wrong there is unpacked every shade of unhealthy leadership, starting with a lack of accountability or authority not exercised in a godly and responsible way to toxic self-serving power. He describes it as a slippery slope from legitimate formal or informal authority to illegitimate other-serving power, then self-serving coercive power, then to the most serious abuses.

Intentions may be entirely positive initially but when the original mandate conferred by the church’s overseeing body is exceeded this can result in pressure by leaders and those around them to get people to achieve the leader’s goals. Unquestioning agreement is expected on the basis that the ends justify the means.

In some situations, for example church plants and independent churches, both internal and external scrutiny may be hard to achieve. “It is easy to sympathise with leaders, who, in the face of unsustainable expectations step outside their legitimate authority to get the job done …. exercise power that isn’t rightfully theirs and the church won’t question it but rather allows them to act unaccountably” pp.38,39. However, after a moment’s reflection we might see this is exactly where spirituality and dependency on God should occur, rather than succumbing to that “inbuilt inclination to want to be a free agent.” p.70.

Honeysett identifies four critical features of servant leadership that help avoid the misuse of power and position:

Accountability. Plurality. Transparency. Embodiment in the church community.

Episcopal (or other) oversight of leaders and pastors is not a ‘just in case we need it’ resource, rather it is to maintain biblical plurality, transparency, scrutiny and accountability.

So, for instance, in their currently disrupted ecclesiology, Anglican churches might ask of their clergy ‘how are you going to lead us now that there’s a battle on?’ The stakes are high - will it be to resort to ‘command and control’? (At this point perhaps check whether Jesus altered his ‘shepherd’ style as things progressed.)

If I am a Ieader I might ask ‘is serving the body, that is, “working with people for their progress and joy in the faith” p.12 reflected in my diary and current thinking or am I more energised at connecting (or arguing) at clerical and episcopal level?’ If my energy and time is focused more on a clerical and peer level than sheep level it may deflect my attention from caring adequately for the sheep. In the Apostle Paul’s mind the shepherd role (elder, overseer, bishop) is not reactive but always proactive, “stewarding grace gifts from God.” p.11. The danger, at this time, is that there is a whole other organisational level operating separately to ordinary members at congregational level.

Ideally, Honeysett says, accountability is within the local congregation plus close networks and denominational structures. In the face of dysfunctional institutional authority, and amid the shuffling of leaders generally, the responsibility must lie with churches and church leaders to actively seek new relationships and support and ensure accountability.

Against a background of suspicion of organised religion and institutions and the culture being more than ready to protest when personal identity is threatened by those who have power, Marcus Honeysett’s contribution helps us to understand what godly leadership is, the importance of how decisions are made and who makes them. His book should be required reading for all Christian leaders who seek to exercise appropriate power in a godly, transparent and accountable manner.

Our prayer should be for those who serve that they “serve by the strength that God supplies in order that in everything God may be glorified through Jesus Christ” (1 Peter 4.11) recognising that “if anyone aspires to the office of overseer he desires a noble task.” (1 Timothy 3.1).