Editorial

“We want you to know, your majesty, that we will not serve your gods or worship the image of gold you have set up”. Daniel 3:18.

“…if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.” Romans 10:9

What is a “confessing Anglican”?

This term, and its variant “confessional”, has been used for some time by Gafcon, for example in the Jerusalem Statement of 2008:

“It is a confessing fellowship in that its members confess the faith of Christ crucified, stand firm for the gospel in the global and Anglican context, and affirm a contemporary rule, the Jerusalem Declaration, to guide the movement for the future”.

The Plano Statement of 2025 uses similar language in saying:

“Gafcon is a confessional fellowship of Anglicans held together by the theology, liturgy and vision of the Reformation Formularies.” (See more on Gafcon 25 and the Plano Statement in our March 2025 News section).

This word, though not explicitly referenced, carries connotations of the Lutheran “Confessing Church” associated with Dietrich Bonhoeffer in 1930’s Germany. As a new film about his life has just been released, it’s worth thinking again about that time and what we can learn from it today.

The word “confessing” carries two main meanings. The first is about theological interpretation. Is the Bible, and theological writing that comes after it, an essentially human enterprise, just recording different opinions about God and how to live, and commenting on them, as an academic exercise, and perhaps as a way of following one of a number of “spiritual path” options? Or is the Bible actually God’s truth revealed graciously to humanity, culminating in calling humanity to repentance and faith in Christ and following him as Lord? As Anglicans we know, sadly, that many in the established churches take the first of these viewpoints, while the “confessing” Christian is one who takes the second option – believing and acting on the gospel!

Eric Metaxas’ biography of Bonhoeffer (Nelson, 2010) puts it like this:

“Theological liberals…felt it was ‘unscientific’ to speculate on who God was; the theologian must simply study… the texts and the history of those texts. But the Barthians [followers of neo-orthodox theologian Karl Barth] said no: the God on the other side of the fence had revealed himself through those texts, and the only reason for these texts was to know him.” [Metaxas, Bonhoeffer, p61].

There continues to be a battle for orthodox, “confessing” Anglicans today in this area of theology. Many theological colleges and Diocesan lay training courses follow a non-confessional approach, often interpreting the Bible in service of a human agenda rather than listening to its teaching and applying it in faith and obedience. But it would be a mistake to limit the implications of being a confessing Anglican to theological debate. For Bonhoeffer and his friends, confessing Christ involved a battle of worldviews and politics in the world outside the church bubble, to the extent that Bonhoeffer would lose his life.

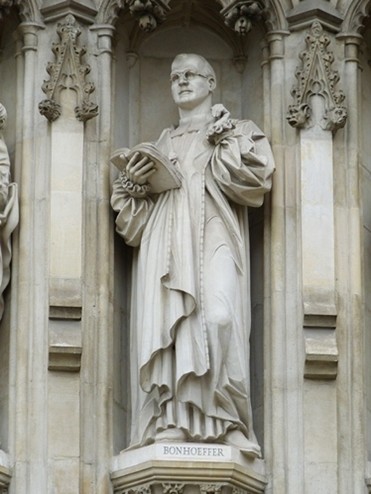

Statue of Dietrich Bonhoeffer at Westminster Abbey

Statue of Dietrich Bonhoeffer at Westminster Abbey

It became clear to many German Christians in the 1930’s that the German state under Nazism was going beyond its God-given role to ensure law and order and freedom for the gospel and was instead becoming cruelly repressive towards certain groups (especially Jews), and denying Gospel freedom. How to respond? Some of the mainline Lutheran leaders in the 1930’s believed that by going along with the Hitler government, including explicit demands for ‘racial purity’, displaying swastikas in church, etc (M, B p171), they would be able to ‘influence from within’, at least ensuring some kind of Christian presence and voice within government.

Others thought it best to be politically neutral, but continue to preach the gospel in churches. The church could try to maintain good relations with the state, perhaps quietly assisting victims of state repression, without directly confronting the state, and praying that it would return to functioning as God intended. Bonhoeffer advocated a more faithful way: not “bandaging the victims under the wheel” but “putting a stick in the spokes of the wheel”, in other words, “taking action against the state to stop it from perpetrating evil” (M,B p154).

For Bonhoeffer, to take such a step would mean the church was “in statu confessionis” – this Latin phrase (meaning ‘in a state of confession’) referred back to the “here I stand” attitude of original Lutheranism: standing on the gospel of Jesus Christ at a time of crisis when a choice for good or evil is called for. Bonhoeffer saw that not to take such a stand was to legitimise wrong, while to take a stand, to declare that the church was no longer supporting the state but opposing it, actually invalidated the state’s legitimacy.

Initially Bonhoeffer was part of a project to build a large coalition of Lutherans standing against the pro-state “German Christians”, spelling out again the basics of the historic Christian faith against the theological contortions of the Nazi compromisers. But the result, the “Bethel Confession”, was so watered down that Bonhoeffer refused to sign it. Eventually he and a minority group led by theologian Karth Barth produced the “Barmen Declaration”, the product of a “Confessional Synod”. This Statement (M, B p222-226) saw the necessity to break away from such compromise and form a “confessing” church, not leaving Lutheranism, but being free of any allegiance to both corrupt State and Church which prevented the full outworking of the confession of Jesus Christ as Lord.

However, by 1938 Hitler was so popular and apparently successful that Barth had fled to Switzerland, and even many of the confessing church pastors took the oath of allegiance to Hitler. Some “were tired of fighting, and they thought that taking the oath was a mere formality, hardly worth losing one’s career” (M, B, p308). Others took a stand, and began to be arrested and imprisoned. War was inevitable, and for Bonhoeffer and a small number of others, the monstrous evil being unleashed meant moving from theoretical confession to active resistance: “we were resisting by way of confession, but were not confessing by way of resistance” (M, B p361). Combining private, spiritual allegiance to Christ and biblical truth with practical compromise with the world would be found out by the crisis of the situation. The cost of true discipleship would involve full surrender to Christ, even if this may mean suffering and death.

Confessing Christ as Anglicans today involves insisting on the truth and authority of Scripture against liberal theologies. But this is not all. We recognise that we can all be tempted to deviate from God’s word when public adherence to that word brings ridicule and even persecution from the powers of the world. Gafcon, led by godly bishops with experience of such persecution, encourages us as a fellowship to humbly confess Christ, not just in church, but also where necessary standing against ungodly values of the culture and even the state, whatever political colour.

Join

If you are committed to biblically faithful Anglican mission in Great Britain and Europe, and developing a vibrant movement for faithful confessing Anglicans worldwide, please join Gafcon GBE.

Gafcon GBE

Christ Church Central

The DQ Centre

Fitzwilliam Street

Sheffield

S1 4JR